Music: A Sequence of Ten Cloud Photographs

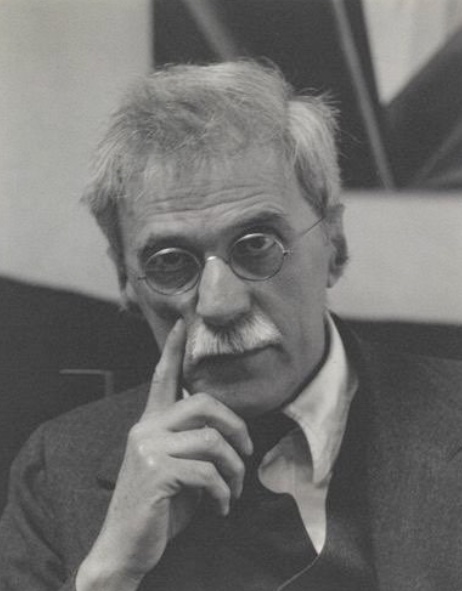

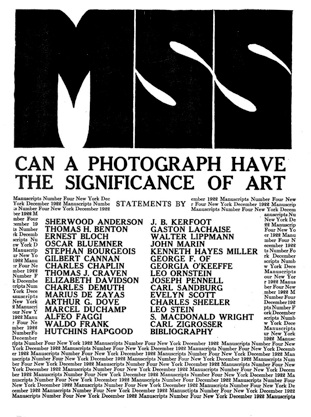

One hundred years ago, Alfred Stieglitz (1864-1946) considered the father of American Photography, invited his protege Paul Strand to edit the 1922 edition of the publication Manuscripts (MSS.) Strand and Stieglitz posed the question: Can a photograph have the significance of art? An invitation was sent out to 40 prominent people in the arts to respond. This question, which graced the cover came at a time when American artists were attempting to forge a distinctively modern style, proclaiming the machine age as their era. However, when artists of this period were producing paintings with streamlined depictions of urban and industrial landscapes, photographs of the same subjects were not necessarily considered art. Stieglitz, since the late 1890’s, had been trying to convince the art world otherwise. He argued that the camera was not just a machine that took photographs, it was a tool for artists just like a paintbrush. Nineteen Twenty-Two was the moment Stieglitz and Strand launched the question in order to provoke a dialogue with the luminaries of the art world, forty of whom responded. Among those who replied were Marcel Duchamp, Carl Sandberg, Georgia O’Keeffe, Waldo Frank, and the composer Ernest Bloch.

Waldo Frank’s submission to MSS came early in 1922. It provided an unexpected and now-famous provocation for Stieglitz, who summed it up a year later:

… Waldo Frank,—one of America’s young literary lights, author of Our America, etc.—wrote that he believed the secret power in my photography was due to the power of hypnotism I had over my sitters …

…It happened that the same morning in which I read this contribution, my brother-in-law (lawyer and musician) out of the clear sky he announced to me that he couldn’t understand how one as supposedly musical as I could have entirely given up playing the piano.

…So I made up my mind I’d answer Mr. Frank and my brother-in-law. I’d finally do something I had in mind for years. I’d make a series of cloud pictures. I told Miss O’Keeffe of my ideas. I wanted to photograph clouds to find out what I had learned in 40 years about photography. Through clouds to put down my philosophy of life—to show that my photographs were not due to subject matter—not to special trees, or faces, or interiors, to special privileges—clouds were there for everyone—no tax as yet on them—free.

…So I began to work with the clouds—and it was great excitement—daily for weeks. Every time I developed I was so wrought up, always believing I had nearly gotten what I was after—but had failed. A most tantalizing sequence of days and weeks. I knew exactly what I was after. I had told Miss O’Keeffe I wanted a series of photographs which when seen by Ernest Bloch (the great composer) he would exclaim: Music! Music! Man, why that is music! How did you ever do that? And he would point to violins, and flutes, and oboes, and brass, full of enthusiasm, and would say he’d have to write a symphony called “Clouds.” Not like Debussy’s but much, much more.

…And when finally I had my series of ten photographs printed, and Bloch saw them—what I said I wanted to happen, happened verbatim. 1

Bloch saw these photographs in Stieglitz’s gallery in May or June 1922. This well-known episode was an affirmation for Stieglitz that photography, like music, can express the human soul. This account by Stieglitz has become a widely accepted event in the annals of photography. Bloch did not write a symphony called “Clouds,” as Stieglitz recounted, but did write evocative pieces for the piano in 1922-23 including Poems of the Sea, Five Sketches in Sepia, Nirvana and In the Night.

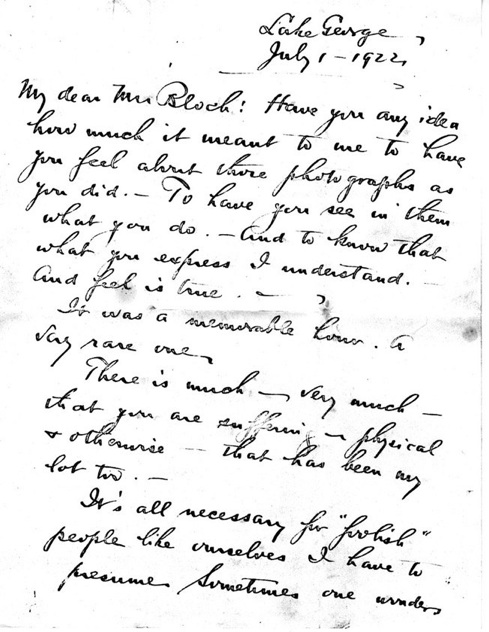

A month after the meeting with Bloch, Stieglitz wrote him a letter from Lake George, in upstate New York, on July 1, 1922:

Stieglitz’s letter shows that he felt a deep kinship with Bloch. They had met several times previously, beginning in 1916 when Waldo Frank introduced them shortly after Bloch first arrived in America.

The leap from clouds to music was natural for Bloch because of his interest in and comfort with Synesthesia (the ability to experience something with one sense and feel it with another) but the decision to consider the results from a camera to be significant art would have required a major conversion. Bloch came from a tradition of deep skepticism of the “machine” (the camera) in relation to artistic creation. What led to his enthusiastic and dramatic change?

Bloch in Europe

To understand this shift in attitude, it’s important to understand Bloch in the pre-WWI era of Paris and Geneva. Bloch began full-time music studies at the Geneva conservatory with Émile Jaques-Dalcroze at the age of fourteen. Between 1896 and 1904, he traveled to Brussels, Frankfurt, Munich, and Paris, where he studied both violin and composition with several prominent teachers, as well as absorbing the music of Wagner, Mahler, Mussorgsky, Debussy, Richard Strauss and César Franck, among others. Bloch met Debussy in 1903 during his stay in Paris. Debussy represented the modern future of music. His groundbreaking Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune (1894) focused purely on the evocation of mood. It was inspired by the poem of the same title by the French Symbolist poet Stéphane Mallarmé. Mallarmé believed that music, by its very nature, suggests synesthetic analogies. Debussy was a pioneer of the use of orchestral color to generate mood and synesthetic expression. This is the environment within which Bloch came of age as a composer.

Bloch became predisposed to find synesthetic connections in art, especially as a means of tapping the authentic soul. The historian, Mike Weaver explored this concept in his 1996 article “Alfred Stieglitz and Ernest Bloch: Art and Hypnosis,” in which he places Bloch in the era before WWI in Paris and Geneva. He describes the fascination among artists and musicians of this era with synesthesia, hypnosis, and the new theories of Freud and Jung regarding the unconscious and its relationship to music and artistic creation. This was new, uncharted territory in which Bloch flourished. In Geneva there was tremendous fascination with the public events of a hypnotist named Emile Magnin, who presented dance and music performances by a Madame Magdeleine G. Under hypnotic influence, Magdeleine (a non-musician, non-dancer) performed extraordinary interpretive dances to music. Magdeleine appeared to have been a “synesthete.” (Synesthesia is also classified as a neurological condition where stimulation of one sense leads to automatic involuntary experiences in another sense.) Weaver states:

Ernest Bloch saw Magdeleine G. just once, possibly in August 1903 in a Geneva studio where she performed to music not only by Wagner, Chopin and by Émile Jaques-Dalcroze, one of Bloch’s teachers, but also by Bloch himself, who contributed a testimonial to Magnin’s book, L!Art et l!Hypnose, 1904. He seems to have accompanied her at the piano, discovering things about himself in his own symphonic piece – aspects of his racial origin of which he had been more or less unconscious up until then. It was this that really interested him—the emergence of his subliminal self in relation to Magdeleine’s, not knowing exactly whether he was projecting it onto her or that she was reflecting it back at him…2

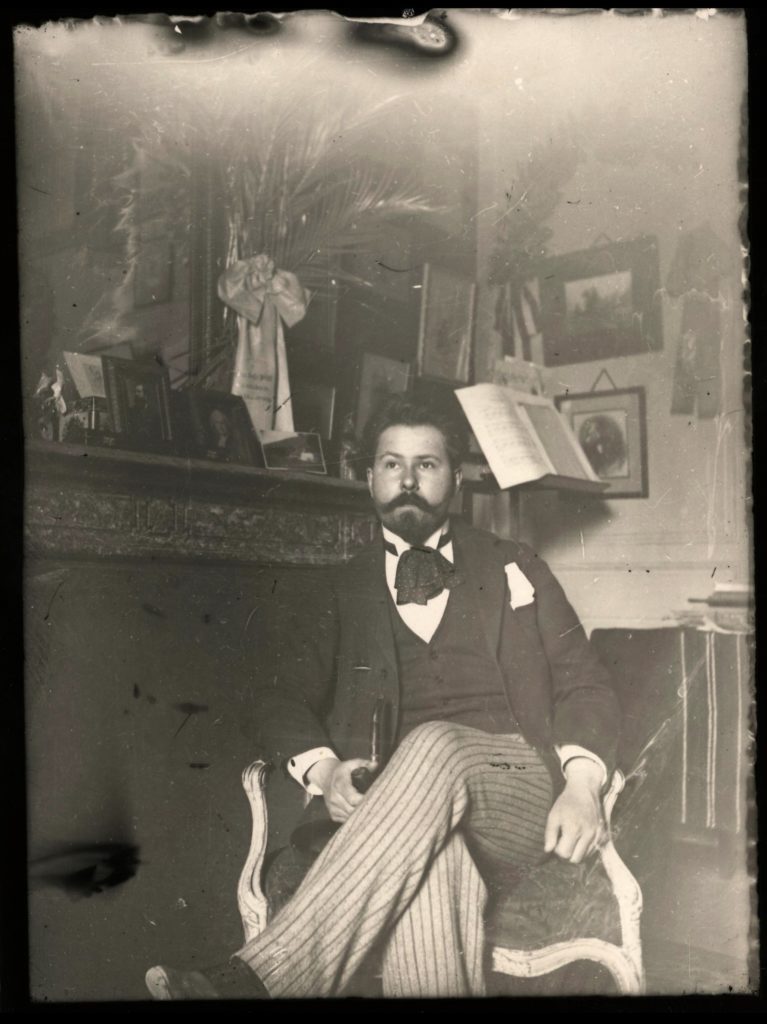

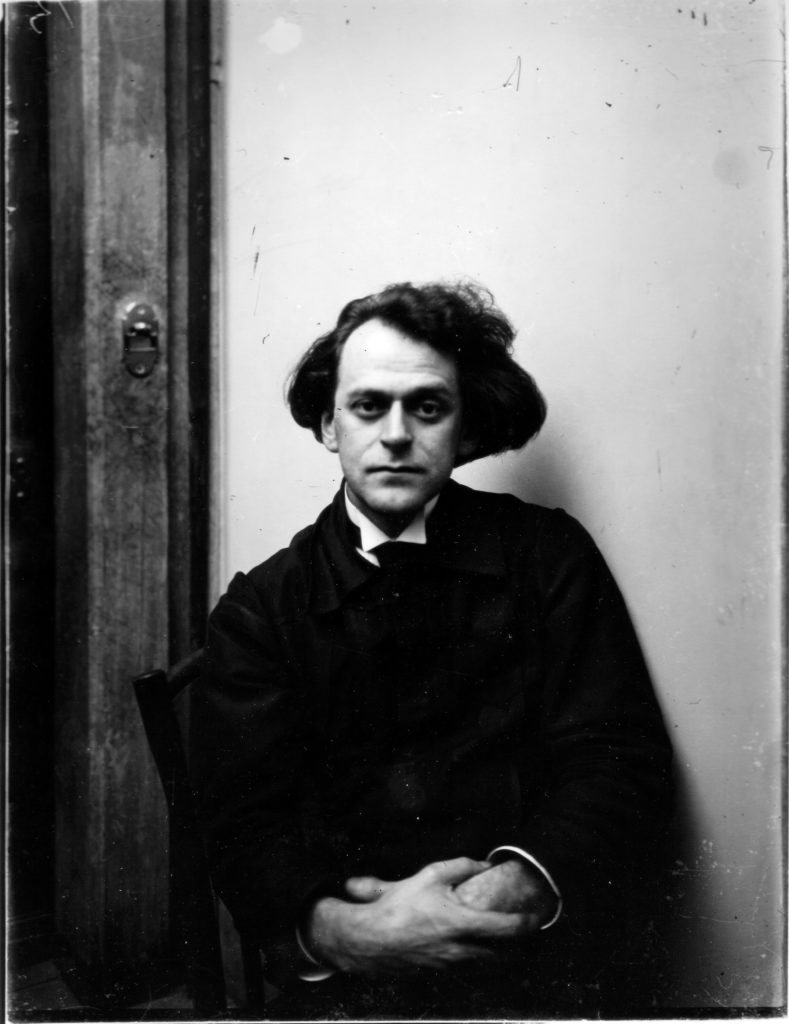

Bloch’s fascination with Magdeleine G. was confirmed by a self-portrait done in Geneva early in 1916. On a wall behind above his left hand is a print of her dancing.

Detail, Self-Portrait with Crucifix, Geneva, 1916

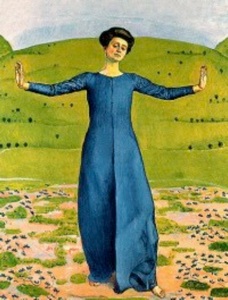

On the same wall to Bloch’s right are two small prints by the Swiss painter Ferdinand Hodler. One, a female figure in a frontal pose appearing to be in a rhythmic dance movement, shows Hodler’s fascination with another convergence of the arts, Eurythmics. Eurhythmics, a teaching method involving the harmonization of mind and body and the expression of individual body rhythms, was a concept central to the theories of Émile Jaques-Dalcroze, Professor of Harmony at the Geneva Conservatoire with whom Bloch had studied and knew well.

Jaques-Dalcroze and Hodler were friends and his paintings consistently incorporate a visualization of the concept of Eurythmics.

As Bloch’s reverence for Debussy, his interest in Hodler, as well as his fascination with Magdeleine’s abilities revealed, the synesthetic response between music and visual art was well developed in Bloch by the time he arrived in America in 1916. Seeing clouds as music? No problem. The much bigger obstacle for Bloch was to see the camera as a valid tool to express the soul.

Bloch Arrives in America

Ernest Bloch was in difficult financial straits at his home of Geneva in 1916 and seized on the offer to conduct for the American tour of an interpretive dancer, Maud Allan. Bloch carried a letter of introduction from influential French writer Romain Rolland to Waldo Frank in New York, who then helped Bloch by commissioning an article for the The Seven Arts magazine. The magazine (which Frank co-edited) was a center for interest in the new ideas of Freud and Jung regarding the unconscious and articles were written about the separation between art and life in modern society. Frank was enthused about Bloch whose music Frank felt was a powerful antidote to this break between art and society. Frank wrote that Bloch was “ruthlessly in love with truth when it is hard to bear.” The composer created a music emanating “from the trammels of a most human life,”….3 In a few months the Maud Allan tour collapsed. But by December of 1916 the Flonzaley Quartet performed Bloch’s First Quartet, and during the next few years as Bloch taught in New York, his works were performed numerous times. This included his Three Jewish Poems in Boston under Karl Muck and at Carnegie Hall in 1918 where Bloch himself conducted his Symphony in C Sharp. In 1920 Bloch was named the founding Director of the Cleveland Institute of Music.

“Man and Music,” the article by Bloch that Waldo Frank commissioned and translated for The Seven Arts, was published in 1917. In the article Bloch presented his beliefs regarding music, art, and the importance of expressing the soul. He contrasted this with mechanical perfection and mechanical inventions:

… and serious composers persist in the obsession with technique and procedure. They discuss and argue; they laboriously create their arbitrary, brain-begotten works, while the emotional element – the soul of art – is lost in the passion for mechanical perfection.

… Art is the outlet of the mystical, emotional needs of the human spirit; it is created rather by instinct than by intelligence; rather by intuition than by will… at the present time the world of art is divided into two great currents. The lower one is that of the masses; their facile taste is sinking with the love of platitude and the weight of mechanical inventions – phonograph, pianola, cinematograph. The other current is that of the “high brow.” With perverted taste, it looks at art as a luxury, as a purveyor of rare sensation, as a matter of intellectual acrobatics. 4

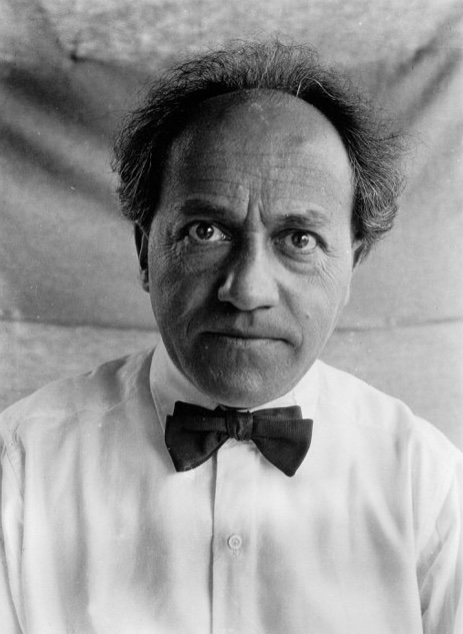

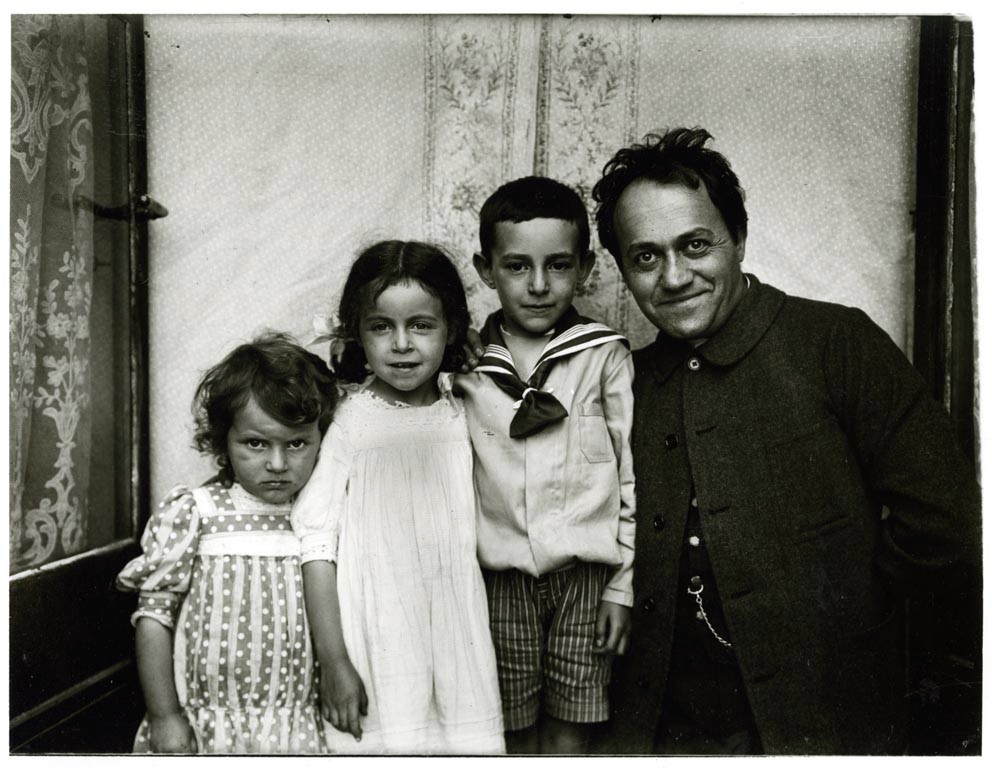

Bloch felt “the machine” and “mechanical perfection” to be antithetical to the expression of the soul. He had, however, been enthusiastic about the camera since he was a teenager. Using a variety of cameras he ultimately producing over 6,000 negatives in his lifetime. He learned to develop and contact print his negatives and placed them in albums to show friends starting as early as 1897.

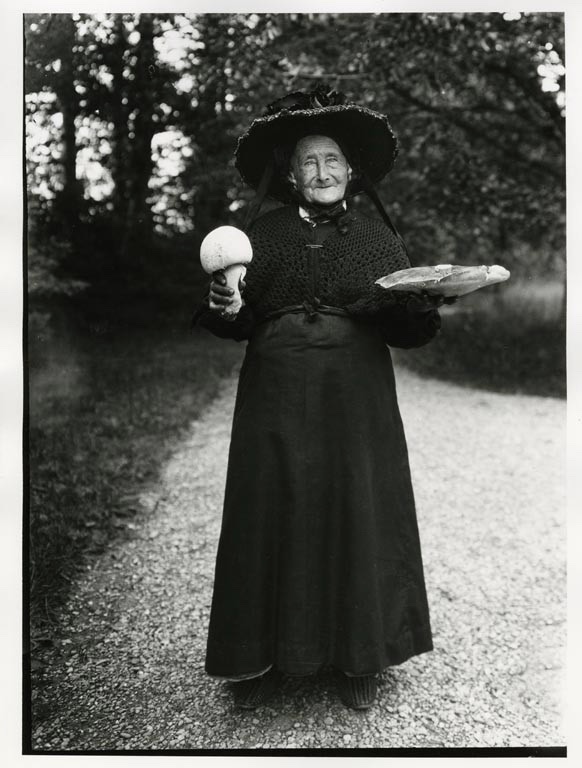

He approached photography with a meticulous craft both in technique and framing. His work ranged from self portraits, pastoral landscapes, and wonderful portraits of his family, fellow musicians as well as farmers who he met on his many hikes in the countryside.5

When Bloch arrived in America in 1916 he had used the camera extensively with meticulous care as a diary and recording device. However, the thought of the “camera” as a tool for significant art expressing the soul would have been foreign to him.

Bloch Meets Stieglitz

It was Waldo Frank who introduced Bloch to Stieglitz a few months after Bloch first arrived in New York in 1916. Bloch met Stieglitz several times before the famous 1922 “Clouds Photograph” meeting. In addition to at least one and probably more visits to Stieglitz’s gallery, Bloch also attended Saturday dinners with Stieglitz and O’Keeffe at the Far East China Garden, a restaurant at Columbus Circle in New York. Stieglitz and O’Keeffe typically had groups of twenty artists and literary friends in discussions following dinner.6

What accounted for the radical transformation of Bloch, from 1916-1922, to seeing—the machine—the camera, as a tool to create significant art? He was, after all, very skeptical of the “lower current” of art, in his 1917 article. What happened?

Bloch himself told the story of his conversion many years later. In 1950, Bloch was teaching a six-week summer course at the University of California at Berkeley. Albert Elkus, chair of the Music Department, hosted a dinner for Bloch. At the dinner table, Albert’s son Jonathan, 18 at the time, recounts Bloch telling this story:

At a dinner in New York Bloch was giving his host Alfred Stieglitz every reason why photography could not be considered art – why photographers, hence could not be considered artists. “Fine,” said Stieglitz, “meet me at my (gallery) early Sunday morning and we’ll photograph together.” They met and went forth with a Graflex camera and tripod. They stopped at a lower midtown corner whose buildings and sky they both thought promising. Stieglitz set up his camera, focused it, and took a picture. Then he changed plates and without repositioning the camera told Bloch it was his turn. Stieglitz timed the exposure identically. They returned to the studio and each developed his plate in the same chemicals with the exact same timing. Bloch saw at once that his cityscape was drab and lifeless, capturing none of the luster he saw in Stieglitz’s. “But how can this be?” Bloch asked. Stieglitz said, “It is because you do not love it; you do not believe in it.7

To Jonathan Elkus, Bloch appeared to be well-practiced at the story. He probably told it many times in his classes. If the story represents the complete facts we cannot know. Bloch certainly may have dramatized it for effect. However, if it took place on a Sunday morning we can deduce that the Saturday dinner which he refers to probably took place in 1917, at the Far East China Garden, and was attended by the likes of Waldo Frank and probably New York Times mu- sic critic, Paul Rosenfeld, both champions of Ernest Bloch’s music at the time. It may even have been their very first meeting where Frank introduced Bloch to Stieglitz in late 1916, only six months after Bloch had arrived from Europe.

What would this first meeting have been like? Bloch had presented more than one hundred lectures at the Geneva Conservatory on aesthetics as well as music in the years before arriving in America at age 36. He had a highly developed philosophical position that art must spring from the soul and the intuition, not the intellect. Bloch, in the tradition of symbolist artists and musicians, equated the machine and the camera with objective description and the intellect. He was strong willed, articulate, and sure of himself. Both O’Keeffe and Stieglitz, also in the symbolist tradition, felt strongly that music was the purest form of artistic expression. So, if Bloch the musician, stated as he described years later, that photography could not be an art and photographers could not be artists during one of these crowded Saturday dinners, Stieglitz had the ultimate challenge.

One can almost imagine a sense of urgency and opportunity that might have seized Stieglitz. Bloch was a musician and composer from Europe who adamantly felt that the camera could not be a tool of art. His declaration, with his supreme credentials, could not go unchallenged. This kind of statement threatened what Stieglitz had worked for during the last two decades. Bloch would need to be converted.

Whether or not the account of a Sunday-morning outing with Stieglitz taking Bloch out to photograph was entirely accurate, we cannot say. We can say, however, that if Bloch did declare what he described in his story of that dinner, it would have been entirely in character for Stieglitz to respond with the Sunday morning invitation to photograph in order to refute Bloch’s argument. They were both extremely strong willed, stubborn in their beliefs yet similar in their fundamental convictions about art. For example, Stieglitz was steeped in the music of Wagner as a listener and amateur pianist, having lived more than a decade in Germany. Bloch revered Wagner as one of the greatest of all composers. In addition, they both shared a strong belief in rejection of theories, systems, and all “isms.” This Sunday-morning transformation may very well be what happened.

Can A Photograph Have The Significance Of Art?

Later in 1922, Bloch responded to the question posed for the issue of MSS: “Can a Photograph have the significance of Art?” Waldo Frank’s response (printed on page 5 of the issue) claimed that Stieglitz’s “hypnotic powers” contributed to the quality of his portraits. This assertion annoyed Stieglitz and, in part, inspired him to photograph clouds in the early months of 1922. Bloch’s response from later in 1922 (on page 14) included the following:

Of course the progress that photography has achieved in the last few years is remarkable. It seems to me, however, that almost all of these improvements have been made in a more or less technical direction …

Besides his stupendous technique (a knowledge of every detail of instrumentation, an overpowering of the smallest possibilities, taming of the chemical forces, transmutation of imperfections or weaknesses of material into artistic ends) every picture of Stieglitz embodies an idea and makes one think. It exceeds usual photography as far as a great artist exceeds a mechanical piano. The dead camera and all other technical means are only tools in his hands.

He has not only photographed things as they seem to be or as they appear to the “bourgeois,” he has taken them as they really are in the essence of their real life and he sometimes accomplished the miracle of compelling them to reveal their own identity–not even always as they are but as they would be if all their potentialities could emerge freely; and this is the greatest Art because all signs of technique have disappeared for the sake of the Idea!

There are portraits of Stieglitz which condense in themselves a whole “Balzac” character; there are pictures of hands so beautiful that one could cry before them; there are pictures of skyscrapers, and railway and backyards that move you as if all the lives and the tragedies of lives connected with them were written clearly on their features. A picture of a young, healthy, and beautiful girl may make you weep because you feel all what she could be, her infinite potentialities. …and realize that in our actual society all these treasures are probably doomed to death and disfiguration. …

Very truly yours,

Ernest Bloch (Composer, Director Cleveland Conservatory.) 8

In this letter, which was written after seeing Stieglitz’s initial cloud photograph series, Bloch described in detail portraits, hands, and building photographs that he no doubt saw on more than one visit to Stieglitz’s gallery. The key line for Bloch, given his clear predisposition, was “the dead camera and all other technical means are only tools in his hands.” Bloch has certainly been converted by Stieglitz’s photographs. The transition from 1916 was complete. Bloch himself wrote years later in a tribute published in the 1947 Stieglitz Memorial Portfolio:

I shall never forget my too-short meetings with him, so many years ago. They are alive as he is within me. Since 20 years, I have in my courses, almost each year referred to him and quoted a few unforgettable talks we had—not only his marvelous works of art—his interpretations of Life, what he called ‘the machine!’ The ‘machine’ subservient to mans thoughts and visions. His incredible ‘technique’ he never mentioned; it was a tool in his hands, for a higher purpose. What an example of ‘Spirit’ in our present time of ‘Robots’.9

Bloch’s predisposition toward the synesthetic combined with the example of Alfred Stieglitz wielding “the Machine” make it natural to see photographs of clouds as music—details as the sound of instruments from an orchestra. He had already converted Bloch. He knew Bloch’s effusive personality. Stieglitz’s ability to predict the enthusiastic response Bloch might have to the cloud photographs was based on personal knowledge. Stieglitz’s letter following the meeting reveals his thanks but also his feelings of kinship with Bloch. That is what gives Stieglitz prediction of the response such a ring of truth. It is exactly how Bloch was and it is probably exactly what he would say:

Music! Music! Man, why that is music! How did you ever do that? And he would point to violins, and flutes, and oboes, and brass, full of enthusiasm, and would say he’d have to write a symphony called “Clouds.” Not like Debussy’s but much, much more.10

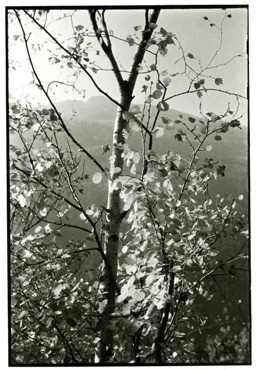

Bloch Photographs the “Soul” of Trees

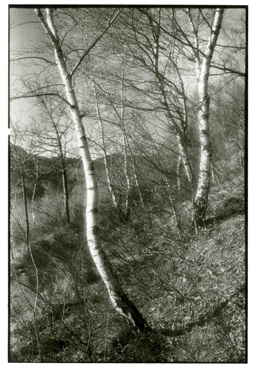

Years later, in 1931, with the financial support of a grant from the Haas family in San Francisco, Bloch began composing his renowned Jewish Sabbath service, the Sacred Service. He chose the quiet Swiss village of Roveredo in the Italian Alps. Bloch was extremely stressed. He was on medication for depression, had insomnia, and was agitated. To relieve his anxiety, he started hiking with his Leica. After days of solitary wandering, he felt that he was communing with the trees. Later he wrote that he found the soul of trees with his camera. He began to do a series of tree photographs. His daughter Lucienne remembers:

It took him a good year to finally get to photographing them, because when I was there (1930) and we were walking he would say “You have no idea how extraordinary these trees are when there are few leaves, and when it’s dark in back so they show up.” He kept saying I’ve got to photograph them. I must make a study of trees.” And that’s when he would point to them and say, ” Now look at this -this harmony of trunks.11

Bloch shared his communion with trees in a letter to Ada Clement in 1931 (Ada Clement brought Bloch to California to head the San Francisco Conservatory of Music):

… after two days of solitary walks, in spite of the snow that is again beginning to fall, I was able at last to speak to the trees, the rocks, the flowers, and they replied to my heart… This is an area of incomparable beauty… no cars, no tourists, no traffic; everything is perfectly harmonious, the scenery is most varied (every walk leads me to another land), the houses are in old stone, picturesque and alive (I will soon send you some photos), the people, all of them farmers, young and old, all simple, real, ambitionless, content with their happy fate, reserved, proud, the best Swiss, perhaps the best people I have met.

… I began to take pictures of one tree and then another amid a disturbing silence. And, all of a sudden, one would have said that the soul of each tree was warming my heart and, in reality, communicating with me. It was a highly emotional moment; I wept! I myself had become a tree—Which is much better than being a man.12

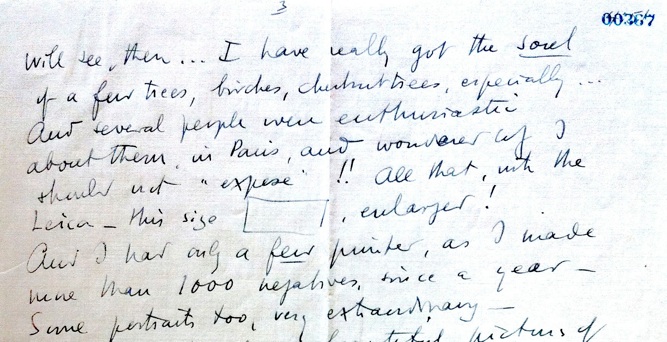

From the same letter of 1931, he also makes clear his enthusiasm for the Leica and what was possible with it. As he says “I have really got the soul of a few trees, birches and chestnuts especially…”

As these photographs and his letter’s make clear, Bloch enthusiastically begins to use the machine – the camera – to make his own personal expressive statement about his world. Although he had enthusiastically used the camera as a diaristic tool since the age of 17 making thousands of photographs, it is only now that he makes this overt effort. The inspiration from Stieglitz is obvious. As a composer one can see his care in framing with the camera, the “harmony” of trunks. Additionally, his ability to see the conformation of trees as an expressive characteristic is clear in this work. Furthermore, Bloch finds music itself in the trees, naming several after composers including Bach, Beethoven, Mozart, and Debussy.

Bloch’s conversion to accepting the camera as capable of expressing the soul exemplified Stieglitz’s arguments about photography. It was a conversion to the acceptance of a tool “a machine” and a significant transformation for Bloch. Steeped in the connections between nature, eurythmic movement, and artistic creation, Bloch was already adept at seeing the synesthetic connections that Stieglitz showed him in his cloud photographs. But the machine was another matter. Finally, in 1931 after decades of taking thousands of photographs as a diary, Bloch took the camera into the realm that he couldn’t have imagined earlier. Like composing, he used photography as an art form that can express the soul.

Eric B. Johnson, March, 2022

Eric B. Johnson, Professor Emeritus, Cal Poly State University San Luis Obispo, where he taught photography and photographic history for over 36 years. A photographer, he began researching editing and printing Bloch’s photographs at the invitation Bloch’s children starting in 1970. Johnson was an undergraduate in the Honors College at the University of Oregon. The Bloch archive was donated to the Center for Creative Photography at the University of Arizona Tucson by the family in 1978. Johnson has continued to work on Bloch’s photography as well as his own photographic career up to the present. Johnson lives in San Luis Obispo, California. ericjohnsonphoto.com

Notes

-

Stieglitz, ‘How I came to photograph clouds’, Amateur Photographer 56 (1923), p. 255.

-

Mike Weaver, “Alfred Stieglitz and Ernest Bloch: Art and Hypnosis, History of Photography, Volume 20 Number 4, Winter 1996, pp. 293.

-

Waldo Frank, Introduction to ‘Man and Music’, The Seven Arts, March, 1917, pp. 493-503.

-

Ernest Bloch, ‘Man and Music’, The Seven Arts, March, 1917, pp. 493‐503

-

Ernest Bloch’s photography was originally researched, edited and printed by Eric Johnson, an undergraduate at the Univ. of Oregon, in 1971. Bloch’s family donated the collection to The Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona, Tucson in 1978.

-

Jonathan Elkus, interview with E. Johnson, Jan. 2011, Berkeley, CA.

-

Jonathan Elkus, interview with E. Johnson, Jan. 2011, Berkeley, CA.

-

Can a Photograph have the Significance of Art,” MSS #4 Dec. 1922.

-

Stieglitz Memorial Portfolio, 1947, Twice A Year Press, New York. Dorothy Norman, ed.

-

A. Stieglitz, ‘How I came to photograph clouds’, Amateur Photographer 56 (1923), p. 255.

-

Lucienne Bloch, Interview with E. Johnson, Gualala, Ca. 1971

-

Letter to Ada Clement, October 1931, p. 2, (Hargrove Music Library, UC Berkeley)