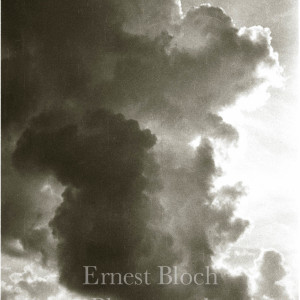

“Ernest Bloch: A Composer’s Vision” was the title of the article I wrote for Aperture magazine in 1972 on my discovery, printing and research of Ernest Bloch’s photography. Below is a brief story about how I unearthed this vast photographic output of over 5,000 negatives by one of the great 20th century composers. It is a story that includes W. Eugene Smith, who listened to Bloch’s music and said “somebody needs to find out about his photographs;” Alfred Stieglitz, who in 1922 was very pleased that Bloch saw music in his photographs of clouds; Minor White, who saw the connections between music and photography and made it possible to publish my article; Paul Caponigro, who helped teach me how to print to get the most out of Bloch’s negatives; Bernard Freemesser, my undergraduate instructor who said “you should do the footwork;” and Suzanne, Ivan and Lucienne Bloch-Dimitroff, his wonderful children who were so generous and supportive of me. And it was Ansel Adams who made it possible for the archive including a large selection of prints I made from Bloch’s negatives, to be placed in the Center for Creative Photography in Tucson, AZ.

Movies with Bloch’s Photographs and Music on You Tube:

Publications:

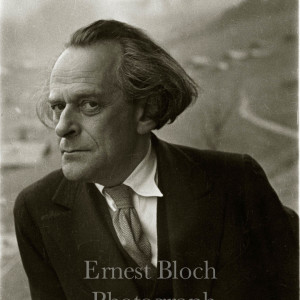

Ernest Bloch Photography

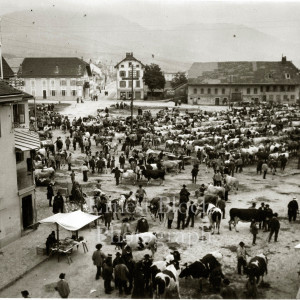

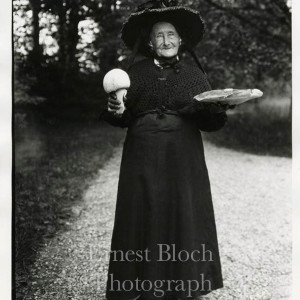

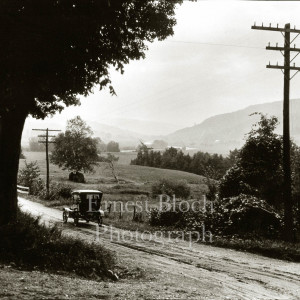

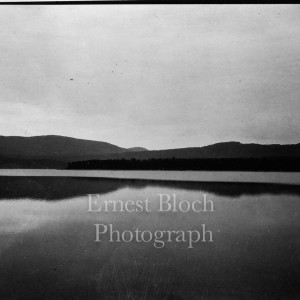

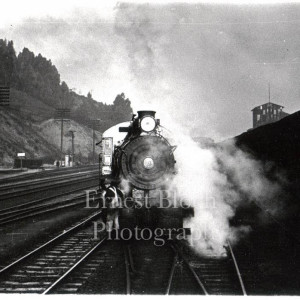

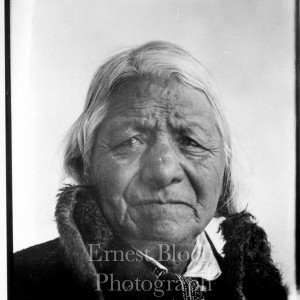

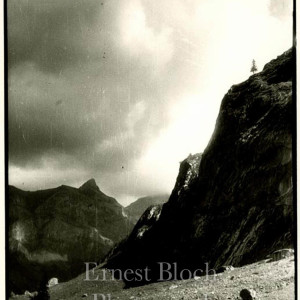

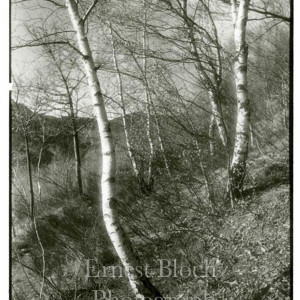

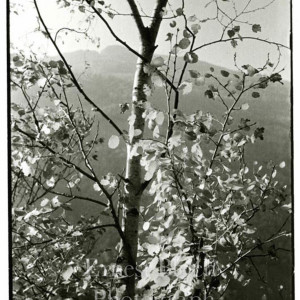

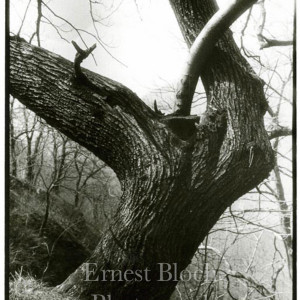

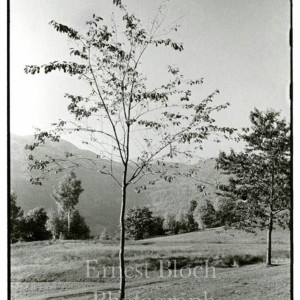

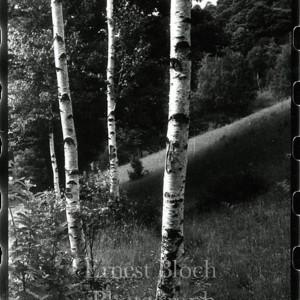

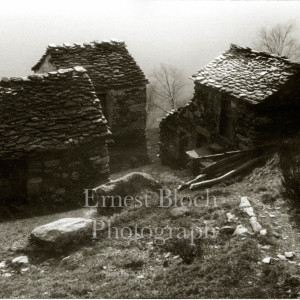

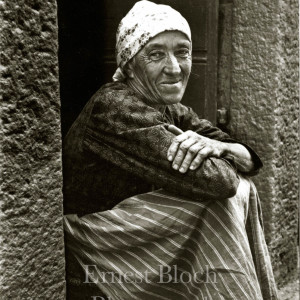

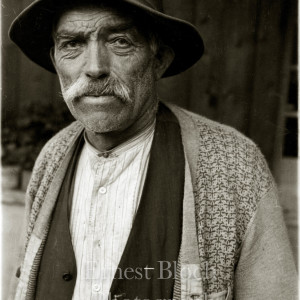

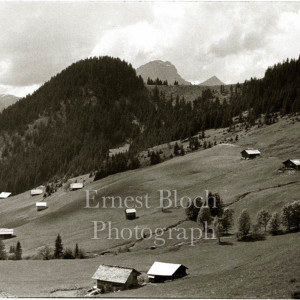

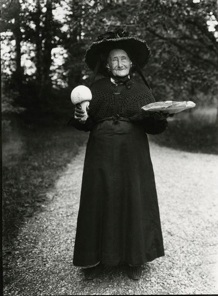

A number of original silver prints I made between 1970 and 1976 from the Bloch collection still are available. Usually only two or three of any image. Silver prints are all 7″x 10″ with the exception of some 11″x14″‘s of the “Mushroom Lady” from 1912 and the “Cattle Auction” from 1898. All silver prints are priced based on the limited quantity left. See Print Sales page for details.

How I Found Ernest Bloch’s Photographs

by Eric B. Johnson

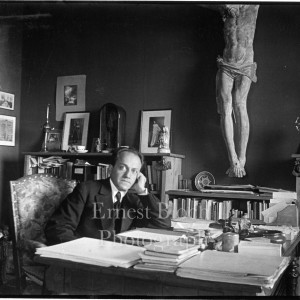

Between 1970 and 1979 I researched, edited and printed from Ernest Bloch’s’ photographic archive. In 1972, Aperture magazine published my article titled “A Composer’s Vision: Photographs by Ernest Bloch.” This archive and a set of 40 prints I made from Bloch’s negatives are in the collection of the Center for Creative Photography in Tucson, AZ.

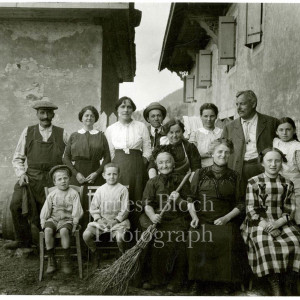

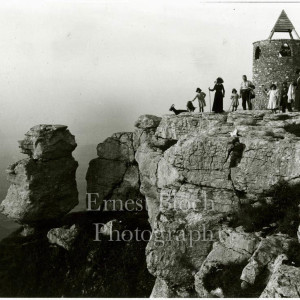

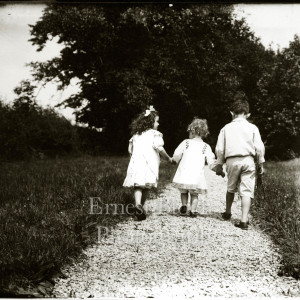

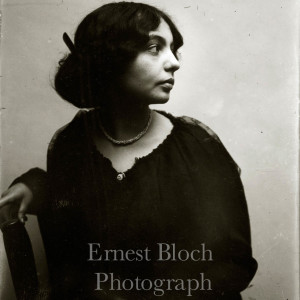

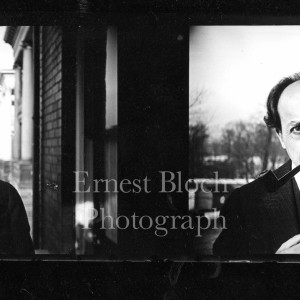

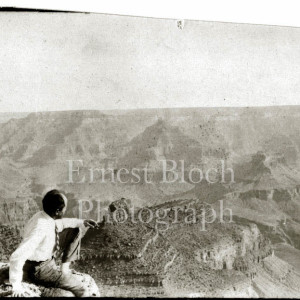

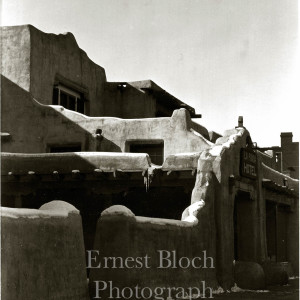

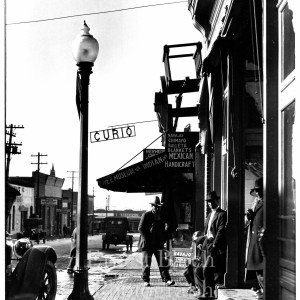

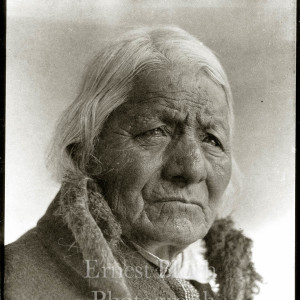

I was encouraged to investigate Bloch’s work by my professor as an undergraduate at the University of Oregon in 1969, Bernard Freemesser. He had heard about the work from W. Eugene Smith who had in turn heard about it from Ivan Bloch, Bloch’s son who lived in Oregon. Smith printed to Bloch’s music. This makes sense when one sees the darkness and drama of Smith’s prints. I contacted Ivan and met him in Bend in 1969. He directed me to his sister Lucienne Bloch-Dimitroff in Gualala, California, near Mendocino. I made contact and was encouraged to come see the collection and my senior year of undergraduate studies at the University of Oregon, 1970-71, was spent on an honors college project with many trips to Gualala focused on Bloch’s work, his music and his photographs. One of my advisors was Robert Trotter, then Dean of Music at U of O. I set up a makeshift darkroom in Lucienne’s outbuilding and began to explore his photographic archives. Most of his thousands of images were in the form of negatives with contact prints and no enlargements. I read from his books on philosophy and music and art. His books had many hand written notes in the margins from many different readings. I listened to his music constantly and immersed myself in Bloch’s expressive and intellectual mind and work for most of a year. I was 22 years old.

Basically, the prints you see of his work are the prints I made in his spirit. They are, as Ansel Adams would say, a performance of his score; that is, the negative is the score and the print the performance. I visited in New York a couple of times to see Suzanne Bloch, his other daughter, who taught Lute at Julliard. I made contact with Aperture magazine and the article “A Composer’s Vision: Photographs by Ernest Bloch” was printed in November of 1971. I was later to meet Minor White in 1973 as well and discuss the connections between music and photography.

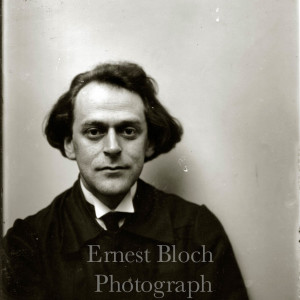

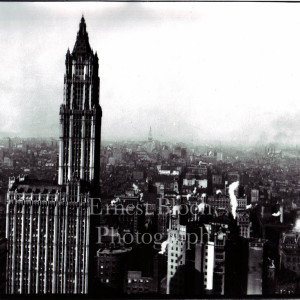

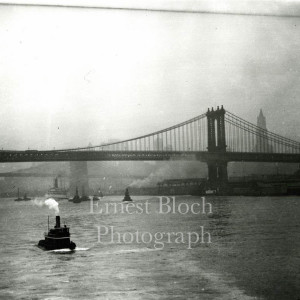

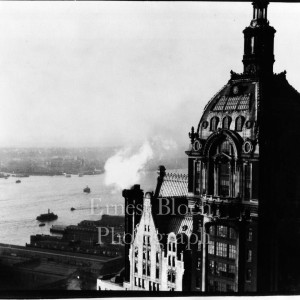

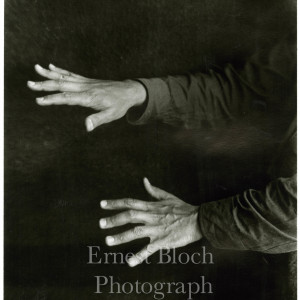

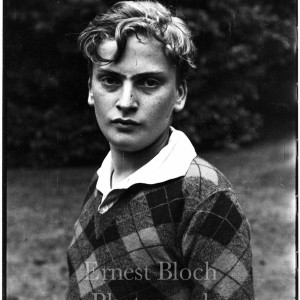

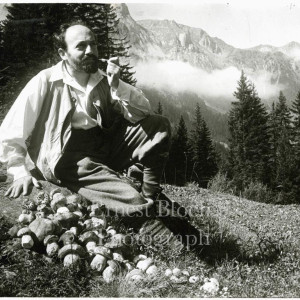

One of my more memorable experiences was printing Bloch’s pictures of a teenage violinist named Yehudi Menuhin. Suzanne encouraged me to send Menuhin a copy and he was kind enough to respond with a hand written thank you note. Ansel also wrote me about Bloch, and I met and talked with him several times along with the great impresario Merle Armitage. Bloch shot most of his pictures on the Leica, so I went through plenty of 35mm material as well as a large number of 4×5 glass plates. He actually started taking pictures as a teenage violin student around 1897. The biggest find of all was when Suzanne found the letter from Alfred Stieglitz to Bloch in her files from her father’s correspondence in 1971 when I was working on the project. I had reminded her that Stieglitz had written about Bloch’s response to his cloud photographs in 1922. That letter from Stieglitz was really pivotal in making all the connections between Bloch’s response to Stieglitz’ cloud photographs and his appreciation of the response. At the University of New Mexico grad program I worked with Beaumont Newhall and Ven Deren Coke while they were teaching. I reprinted many of Bloch’s negatives again while a grad student with better technique and emphasis on tonal range. I remember spending time in Paul Caponigro’s darkroom in Santa Fe where he would tutor me on the printing technique from a Bloch negative. I mounted a show of the prints at the University of New Mexico in coordination with the music department, where his music was also performed. Lucienne and Steve Dimitroff came down in 1977 and spoke on Diego Rivera, for whom they assisted, as well as Ernest Bloch. This was also about the time that the Center for Creative Photography was contacted. Ansel Adams actually made the connection. This would be a few years before he died. The Center in Tucson acquired the entire archive in 1978. The collection, including over 40 prints I made from his negatives, is now in that archive.

So, Ernest Bloch and I go way back. He had a profound impact on me, my career, my understanding of music and emotion. Indeed, I can say that I felt then and now a deep kinship with Bloch and the emotional depths he was able to navigate. I am forever grateful that I was the one who found his work and brought it to public awareness.

2009, the fiftieth year since his death, has been an extraordinary year of remembrance of Bloch’s music and contribution. I am very happy to have made a contribution with my donation to the Library of Congress.

All contents ©2011 Eric B. Johnson —-consent must be given for any reproduction, electronic or otherwise.